Yellow-breasted Bunting Emberiza aureola 黃胸鵐

Category I. Passage migrant, common in autumn and uncommon in spring, and scarce winter visitor to open-country areas, particularly rice fields.

IDENTIFICATION

May 2014, Michelle and Peter Wong. Adult male.

14-15.5 cm. Large bunting often with a relatively loud call. Adult male in breeding plumage has black face and throat, yellow underparts, chestnut breast band, crown and nape, and white median coverts forming a broad band near bend of wing.

Oct. 2009, Michelle and Peter Wong. Adult male.

Males in winter have strongly yellow underparts, contrasting face, indistinct breast band and obvious but buff-tipped white wing panel. The pale tips to the upperpart feathers disappear as winter progresses.

Nov. 2007, Martin Hale. First-winter male.

First-winter males can be identified by obvious rufous on rump or yellow on underparts, buff tinge to throat and upper chest with only sparse and diffuse darker streaks and white in wing coverts that is not as extensive as adult male.

Nov. 2018, Michelle and Peter Wong. Female.

Female has strong head pattern with broad buff supercilium from bill to hind neck, dark border to ear coverts and subdued rufous on rump.

VOCALISATIONS

The typical flight call is a relatively loud and sharp ‘tzik’. Also a quieter and high-pitched ‘tik’.

Recordings of this species on Xeno-Canto are currently restricted due to the potential for use in trapping birds.

DISTRIBUTION & HABITAT PREFERENCE

Like Chestnut-eared Bunting, Yellow-breasted Bunting is restricted to open country, occurring in wet and dry farmland (particularly rice fields), grassland in abandoned agricultural areas, landfill sites and the edges of reed beds. Elsewhere in China it is (or was) a characteristic species of rice fields in autumn (Vaughan and Jones 1913, Byers et al. 1995) and it was recorded in this habitat in HK prior to the demise of rice cultivation (Herklots 1953). Habitat management at Long Valley, which has focused on the creation and management of rice fields, has proved successful in increasing the numbers recorded, with approximately 50% of records since 1999 at this site.

A further 30% of records are from the fish pond and managed wetland habitats of the Deep Bay area. Other records are from agricultural and low-density residential areas in the central New Territories and a variety of other sites, including urban edge areas. Wintering birds occur largely in fish pond areas or at Long Valley, while passage birds are distributed more widely.

OCCURRENCE

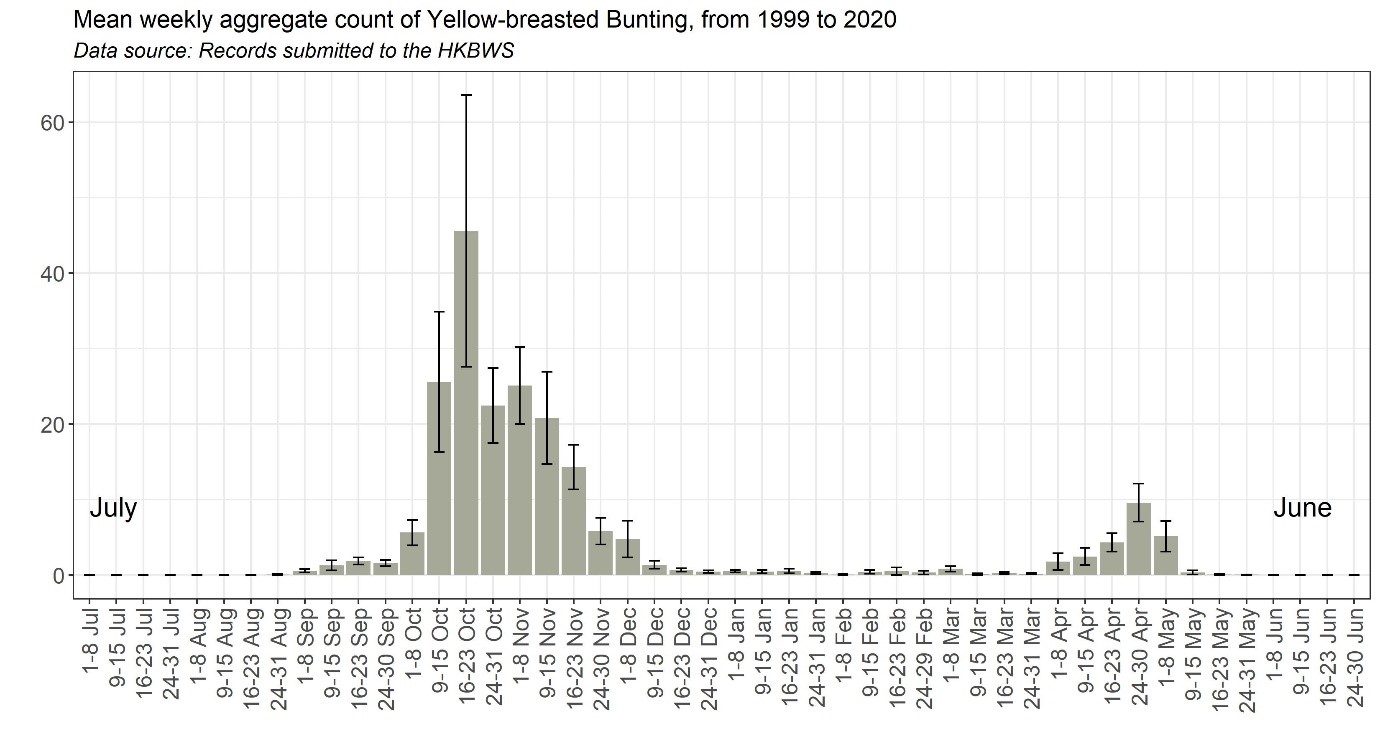

Yellow-breasted Bunting is a passage migrant, common in autumn and uncommon in spring, and scarce winter visitor (Figure 1) to open-country areas, particularly rice fields.

The earliest autumn record of Yellow-breasted Bunting occurred on 25 August 2019. Small numbers are recorded during September and the first week in October prior to the main passage period from the second week of October to the third week of November. By the second week of December most birds have left HK and only small numbers remain during the winter. Spring passage may commence as early as late February but is obvious from the beginning of April to mid-May, with the latest record occurring on 30 May 2016.

The highest count on record is an exceptional 3,000 in a pre-roost gathering at Ping Shan (now part of Yuen Long-Tin Shui Wai) on 19 October 1959. The next largest is of 610 birds over Mong Tseng on 21 October 1994. The highest count since 1999 is 300 at Mai Po on 20 October 2002, with the next highest being 120 at Long Valley on 10 November 2014. The highest spring count since 1999 is 26 on 27 April 2001, while the peak spring count prior was 200 on 18 February 1984 and 2 March 1985.

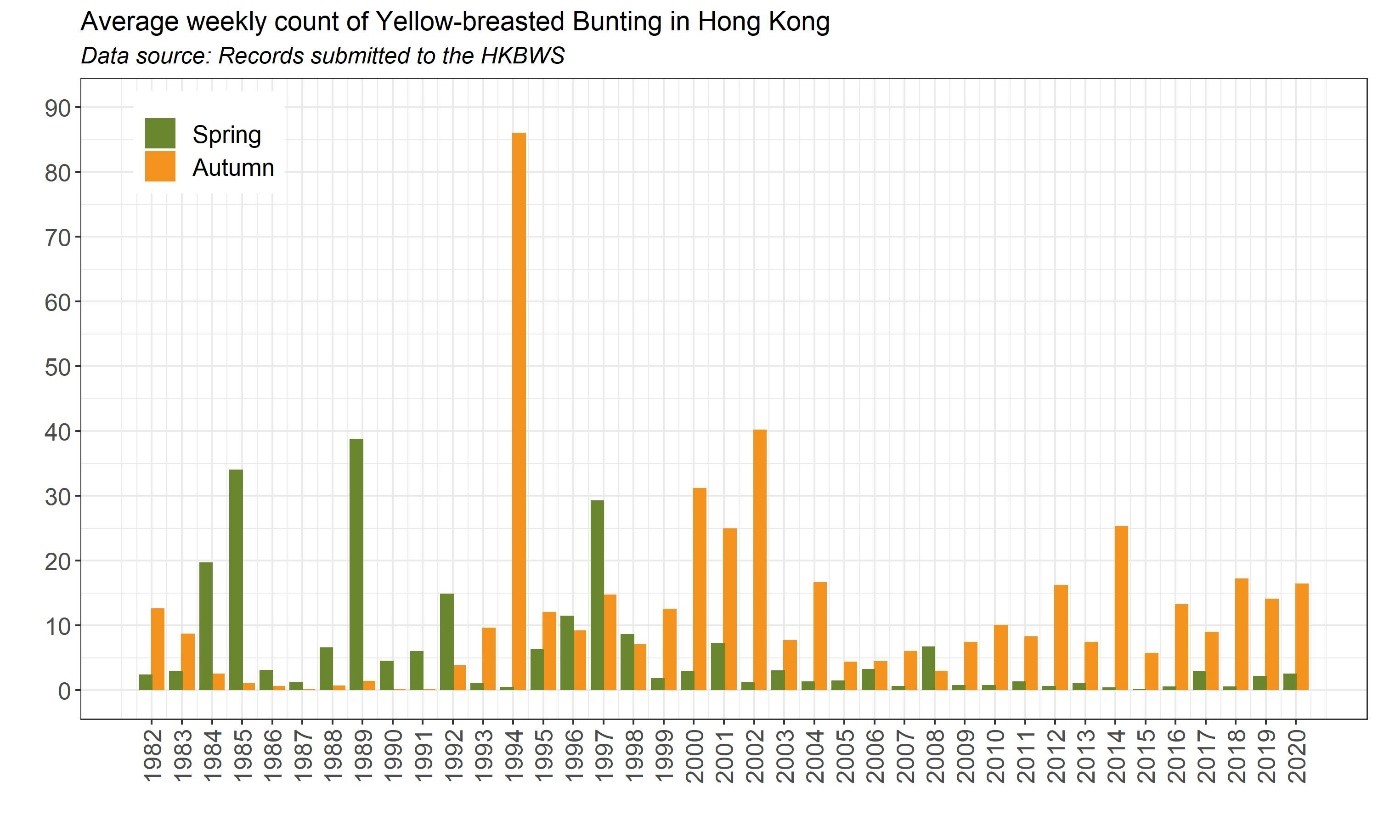

Figure 2, which charts the average weekly spring and autumn counts since 1982, indicates a substantial decline in the number of birds passing through in spring despite increased observer activity. Mean weekly aggregate counts are particularly low in the early spring period suggesting that the population of birds passing through at this time has greatly declined. Although the decline in autumn numbers since approximately 2003 is not so great, this should be set against an increase in observer activity and the provision of favoured rice paddy habitat at Long Valley that provides optimum foraging habitat in autumn.

Whilst the decline can partly be explained by loss of favoured rice paddy habitat, there are still extensive areas of open country in the Deep Bay area suitable for this species. The now well-documented popularity as a culinary delicacy has grown in tandem with rising income levels on the mainland and the numbers of birds trapped has apparently increased greatly.

Swinhoe (1861) described the species as common and Kershaw (1904) and Vaughan and Jones (1913) referred to the large numbers which were netted in the Pearl River delta and sold, to be eaten as “rice birds”. Similarly, Herklots (1937) referred to large flocks passing through HK in October and April and Dove and Goodhart (1955) described flocks of up to 200 birds in autumn and up to 40 birds in spring from 1952 to 1953.

BEHAVIOUR, FORAGING & DIET

Forages in ripe rice in autumn and on grass seeds elsewhere, but no details.

RANGE & SYSTEMATICS

Breeds largely south of the Arctic Circle from western Russia east to Kamchatka and south to northern Mongolia, northeast China and northern Japan; winters in coastal provinces of south China west to the Himalayas and south to Indochina (Byers et al. 1995).

Two subspecies are recognised. The nominate breeds from east Europe to east Siberia, while E. a. ornata breeds further east from south central to southeast Siberia to Japan and northeast China.

Adult male ornata has slightly darker chestnut upperparts and deeper yellow underparts, often with a more prominent and blacker breast band (Shirihai and Svensson 2018), which should be visible on spring birds. Despite this, no birds have been assigned to either taxon. The subspecies also differ in moult strategy, with aureola moulting in central China during early autumn prior to migrating southwards and ornata showing a more conventional Emberizid moult on the breeding grounds prior to migration (Byers et al. 1995). Early autumn birds in HK are presumably, therefore, of the latter form, though this has not been confirmed.

CONSERVATION STATUS

IUCN: CRITICALLY ENDANGERED. Population decreasing, believed to be due to trapping in passage and wintering areas.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Byers, C., U. Olsson and J. Curson (1995). Buntings and Sparrows. A Guide to the Buntings and North American Sparrows. Pica Press, UK.

Dove, R. S. and H. J. Goodhart (1937). Field observations from the Colony of Hong Kong. Ibis 97: 311-340.

Herklots, G. A. C. (1937). The birds of Hong Kong. Part XXVII. Family Fringillidae, finches and buntings. Hong Kong Naturalist 8: 65-72.

Kershaw. J. C. (1904). List of birds of the Quangtung Coast, China. Ibis 1904: 235-248.

Shirihai, H. and L. Svensson (2018). Handbook of Western Palearctic Birds Vol. 2. Passerines: Flycatchers to Buntings. Helm, London.

Swinhoe, R. (1861). Notes on the ornithology of Hong Kong, Macao and Canton, made during the latter end of February, March, April and the beginning of May 1860. Ibis 1861: 23-57.

Vaughan, R. E. and K. H. Jones (1913). The birds of Hong Kong, Macao and the West River or Si Kiang in South-East China, with special reference to their nidification and seasonal movements. Ibis 1913: 17-76, 163-201, 351-384.