Common Kingfisher Alcedo atthis 普通翠鳥

Category I. Common in autumn and winter, scarce in spring and summer; frequents a wide variety of lowland, largely freshwater wetlands, though also forages at the coast. The migrant population is probably much declined.

IDENTIFICATION

Aug. 2008, FUNG Hon Shing. Male.

16-18 cm. Unmistakeable small blue kingfisher. The upperparts and tail are bright azure blue that shows well in flight. The head and lesser and median coverts are turquoise with brighter centres to the feathers, while the loral spot and ear coverts are orange. The underparts are largely orange apart from a white throat. The bill is all-dark in the male, while female has a largely orange lower mandible.

Oct. 2017, Michelle and Peter Wong. Male.

When hovering it shows orange underparts and underwing coverts.

Juveniles have a dull, greenish tone to the crown and wings, a dark breast-band and relatively dull orange face and underparts.

VOCALISATIONS

The most frequently heard call is a high-pitched and piercing slightly downslurred ‘tseee’ uttered singly or in series.

A more varied set of calls are uttered by interacting birds.

DISTRIBUTION & HABITAT PREFERENCE

Common Kingfisher utilises a wide variety of wetland habitats but is found in largest numbers at fish ponds; it also occurs in marshes, mudflats, mangrove edge, gei wai, tidal creeks, open streams and water channels, especially in agricultural areas, and also forested streams and city parks. Most reports are from the Deep Bay area and coastal regions of the New Territories, but it is also found inland and on HK and Lantau islands and is occasionally recorded in Kowloon and on smaller offshore islands.

Between the breeding surveys of 1993-96 and 2016-19 there was a fall in the percentage of occupied 1km squares from 7.3% to 3.0%. The more recent survey recorded it largely in the Deep Bay area and hinterland, with scattered records elsewhere in coastal areas of the mainland New Territories. It appears now to be largely absent in the breeding season in western, central and eastern New Territories and on Lantau, Lamma and HK Islands.

Between the winter atlas surveys of 2001-05 and 2016-19 there was a fall in the percentage of occupied 1km squares from 9.4% to 5.7%. In the earlier survey it was recorded mainly in the Deep Bay hinterland and coastal areas, but also in the northeast and east New Territories, on Lantau and HK Island, and in scattered locations elsewhere. In the more recent survey it had disappeared from HK Island and the eastern New Territories, declined on Lantau and was less numerous in the Deep Bay area.

OCCURRENCE

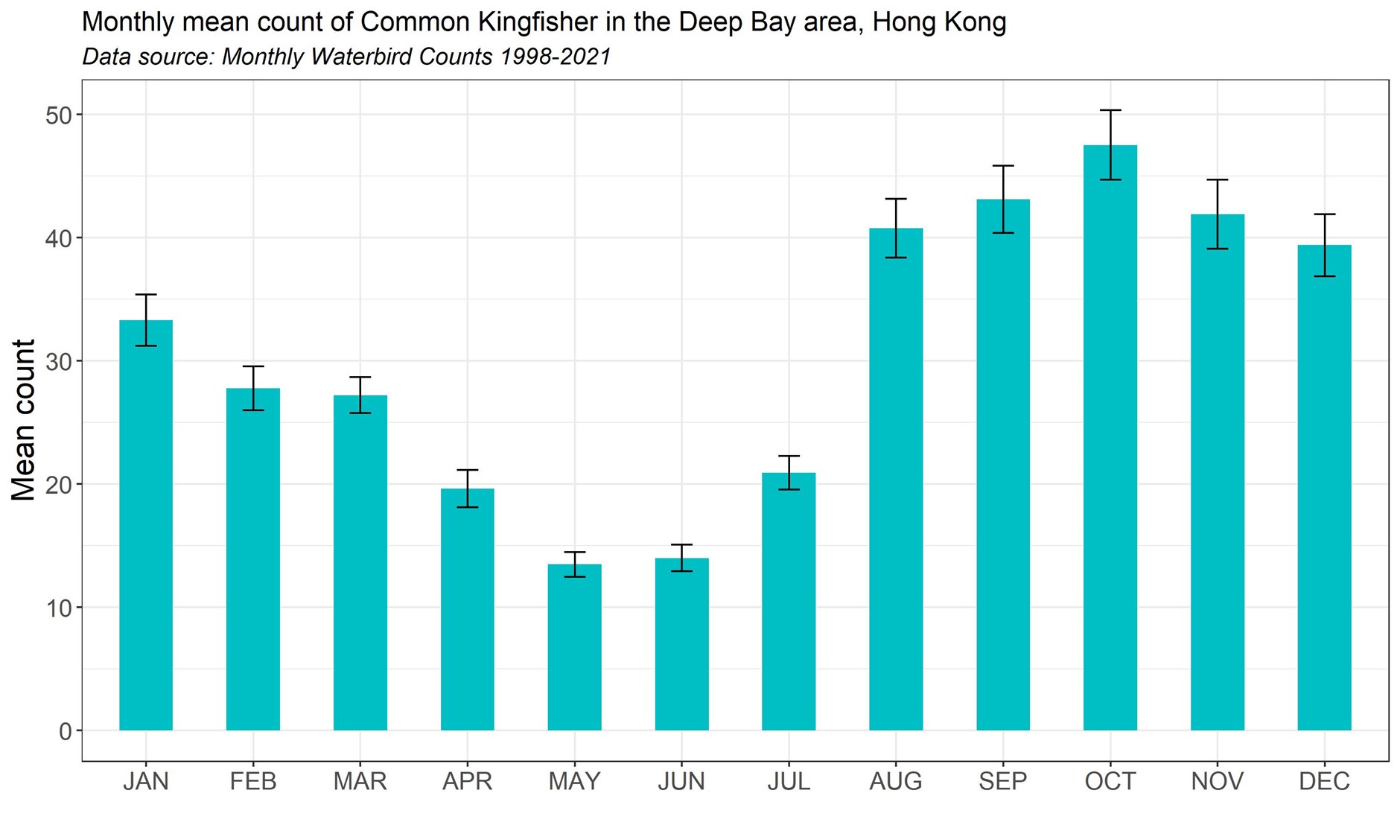

Systematic monthly waterbird counts since 1998 in Deep Bay, the core area of distribution of Common Kingfisher in HK, indicate that numbers are lowest in the breeding season of April to July before climbing to sustained peak from August to December, with highest numbers occurring in October, a pattern indicating passage through HK. January sees the beginning of a decline in numbers that continues until the middle of the year (Figure 1).

The four largest counts of this species were obtained during these coordinated monthly surveys, with the highest being 50 in the Deep Bay area on 16 August 1998. Away from Deep Bay, counts of 10-12 birds have been made at much smaller sites at Sha Tin (18 October 1959), Sai Kung (5 September 1975) and Starling Inlet (25 October and 24 November 1997).

The number of birds (including recaptures) ringed at Mai Po NR each year fell so dramatically from 267 in 1990, the peak year, to 29 in 1996 as to suggest a serious decline, though in view of habitat changes and variations in ringing effort and net-site locations at Mai Po, Carey et al. (2001) stated these figures must be treated with caution. However, the five-year mean of birds trapped is now even lower at approximately 12, and there is a general sense that this species has declined greatly.

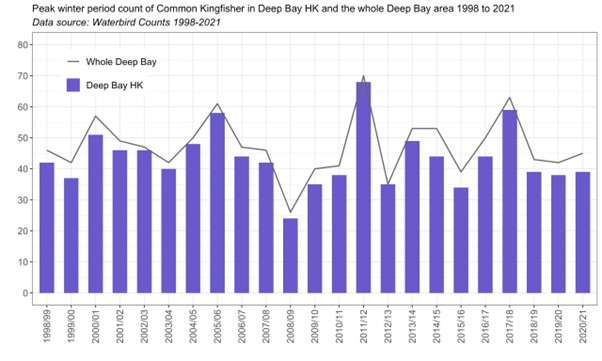

In contrast, the systematic monthly waterbird counts do not indicate a notable fall in the Deep Bay wintering population. Figure 2 indicates broadly similar peak winter counts across the period from 1998 to 2020.

Carey et al. (2001) reported that nearly 90% of ringed birds were juveniles or in their first calendar-year; less than 1% were trapped in succeeding years, and less than 2% were shown to over-winter. A melanistic individual was present at Mai Po on 18 August 1965.

Common Kingfisher was regarded as common in the region, presumably including HK, by Swinhoe (1861), Kershaw (1904) and Vaughan and Jones (1913). Subsequently, Hutson (1931) described it as the commonest kingfisher here, occurring in all months, and until the end of the century there was no indication of a change in status (Chalmers 1986, Carey et al. (2001)).

BREEDING

The breeding season in HK spans the period February-August, and occupied nest holes have been found from February to July. Dependent juveniles have been seen from 13 April to 9 August. HK nesting records are therefore slightly earlier than dates given by Vaughan and Jones (1913) who noted eggs from 12 April to 5 July and considered the species double-brooded in the Pearl River area.

Jones (1908) reported that nests are made in muddy banks, may be a considerable distance from water and are generally two or three feet above the water; the nest hole is not more than 18-20 inches deep.

BEHAVIOUR, FORAGING & DIET

Perches on a variety of objects as it scans the water for prey, and occasionally hovers with fast-beating wings before diving down from up to 6m into the water.

RANGE & SYSTEMATICS

Occurs right across the Palearctic from western Europe and north Africa to Japan, with northerly populations migratory. Winters in southern Europe, the Indian subcontinent and south China south through southeast Asia to the Lesser Sundas (Woodall 2020). In China, a summer visitor to the northeast and present all year in lowland parts of the country, wintering as far north as Beijing (Liu and Chen 2020, Birding Beijing 2022).

CONSERVATION STATUS

IUCN: Least Concern. Population trend unknown.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Birding Beijing (2022). https://birdingbeijing.com/the-status-of-the-birds-of-beijing/ (Accessed 12 December 2023).

Carey, G. J., M. L. Chalmers, D. A. Diskin, P. R. Kennerley, P. J. Leader, M. R. Leven, R. W. Lewthwaite, D. S. Melville, M. Turnbull and L. Young (2001). The Avifauna of Hong Kong. Hong Kong Bird Watching Society, Hong Kong.

Chalmers, M. L. (1986). Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Hong Kong. Hong Kong Bird Watching Society, Hong Kong.

Hutson, H. P. W. (1931). The birds of Hong Kong. Part VI. Alcedinidae The Kingfishers. Hong Kong Naturalist 2: 85-89.

Jones, K. H. (1908). On the nidification of Halcyon pileatus and Turnix blandfordi in Hong Kong. Ibis 1908: 455-457.

Kershaw, J. C. (1904). List of birds of the Quangtung Coast, China. Ibis 1904: 235-248.

Liu, Y. and Y. H. Chen (eds) (2020). The CNG Field Guide to the Birds of China (in Chinese). Hunan Science and Technology Publication House, Changsha.

Swinhoe, R. (1861). Notes on the ornithology of Hong Kong, Macao and Canton, made during the latter end of February, March, April and the beginning of May 1860. Ibis 1861: 23-57.

Vaughan, R. E. and K. H. Jones (1913). The birds of Hong Kong, Macao and the West River or Si Kiang in South-East China, with special reference to their nidification and seasonal movements. Ibis 1913: 17-76, 163-201, 351-384.

Woodall, P. F. (2020). Common Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.comkin1.01