Great Barbet Psilopogon virens 大擬啄木鳥

Category I. Probably a 20th century colonist; now an uncommon, but fairly widespread, resident in fung shui woods and mature secondary forest, largely in the central and east New Territories.

IDENTIFICATION

Dec. 2016, KWOK Tsz Ki.

27-33 cm. A large and brightly coloured barbet that often appears all-dark when seen at a distance. Very heavy yellowish bill, blue-back head, brown mantle and wing coverts and blue green flight feathers and tail. Underparts pale yellow heavily spotted brown with red undertail coverts. Often difficult to see well in the canopy, but very vocal, giving repetitive piercing wailing call, often for long periods.

VOCALISATIONS

Heard throughout the year but most vocal from March to June (Carey et al. 2001). Males and females duet, with the female’s rapidly repeated notes responding to the modulated note of the male.

The male may often be heard alone.

The call most frequently heard is a shrill rattle.

DISTRIBUTION & HABITAT PREFERENCE

Great Barbet is wholly arboreal and is usually to be found high in trees, either on, or more often within, the tree canopy. It has generally been assumed that it requires or at least favours large areas of mature broadleaf forest, though there is actually little evidence to show that it occurs at higher densities in large forest blocks. Indeed the converse may be the case; the largest aggregations noted in recent years have been in edge habitats such as Tai Po Kau Headland and Tai Po Kau Park. Such sites often contain fig trees, notably the two commonest large banyans in HK, Ficus virens and F. microcarpa, which seem to be a favoured source of food (see below). If so, this may explain why Great Barbet has not, at least as yet, benefited as much has might have been expected from the increased area of forest and forest maturation. It may favour patches of mature trees with abundant fig trees, as are often found in fung shui woods and around villages in such areas as Lam Tsuen Valley.

Carey et al. (2001) described Great Barbet as a locally common resident, and the first breeding atlas survey (1993-96) recorded it from 6.4% of squares, largely in the central and east New Territories, but with small numbers in the northeast. Subsequent atlas surveys suggested that the overall range essentially remained similar, and that it had declined in numbers, as it was only observed in 2.8% of squares in the 2016-19 breeding season survey (winter surveys which logged it from 1.3% of squares in 2001-05 and 2.3% of squares in 2016-19 are probably less relevant for this species as it is largely detected by its vocalisations). However, the atlas survey findings do not accord with the increased numbers of both sites and individuals reported in the current century (see below), suggesting that it was particularly well-recorded in that first breeding bird survey when there was no restriction on survey effort.

OCCURRENCE

Great Barbet has a varied history in HK with major changes taking place in both range and numbers over the years. It was first recorded in HK on 20 March 1929, when a pair was found in the Zoological and Botanical Gardens (ZBG) on HK Island. This pair went on to breed and two broods were hatched but ultimately both nesting attempts failed. The first ended with the young being found under the nest tree after heavy rain and the second when the nest tree blew down in a typhoon (Hutson 1930). Whilst this is the first documented record, it may not have been the first occurrence. Hutson (1930) made reference to another observer having ‘heard of several pairs in the New Territories in recent years’. Indeed, Herklots (1933) described Great Barbet as occurring in the Lam Tsuen Valley and at Sha Tin, as well as Aberdeen on HK Island.

Herklots (1953) described Great Barbet as being ‘regular and common’ and made reference to the sound of ‘five, ten or twenty birds calling together.’ This suggests that at the time (perhaps immediately prior to the Second World War - as Herklots’ observations refer almost entirely to the period prior to 1945), it was considerably commoner than it has been since. Whilst hearing five birds at one time would not be unusual today, ten would be exceptional and 20 would exceed the highest count since the formation of HKBWS in 1958. Indeed, Dove and Goodhart (1955) referring to their own observations, largely in the New Territories, in 1952-53 considered that it had almost disappeared and only observed it twice, up to three birds in Lam Tsuen Valley. Perhaps large-scale forest clearance during the Second World War was the cause of this decline.

However, by 1955 to 1957 it appears to have become more common again. Walker (1958) reported up to 12 birds in Lam Tsuen Valley on 30 April (and also recorded single individuals in the ZBG and on the Peak). Great Barbet was still regularly reported on HK Island during 1958-62 but then appeared to have abruptly died out with just three later records of single individuals, at Mount Nicholson in 1986 and 1988 and Aberdeen Country Park on 18 June 1994.

However, following a gap of over 24 years, one was reported from Scenic Villas Drive, Pokfulam on 28 October 2018, followed by observations of two birds at Lung Fu Shan and one on Mount Davis in 2023 (the latter confirmed by a photograph) (eBird 2023). It is notable that all four of these records came from the same area in the west of the island.

The reasons both for its disappearance and recent reappearence on HK Island are unclear; whilst urbanisation might explain its abandonment of the ZBG, it seems unlikely to account for its disappearance from the south side of HK Island (where the areas of forest have increased). However, if it is large trees in edge habitats that are favoured rather than larger forest blocks this gives credence to the suggestion by Carey et al. (2001) that competition with cockatoos and parakeets, none of which penetrate into forest to a significant extent in HK (Andersson 2021), may be an important factor. Against this background, it is probably too early to predict whether the recent records will lead to recolonisation, but Andersson (2021) considered that there were many trees in the Country Parks of eastern HK island that were approaching the age and size that would render them suitable for nest cavities to be formed and used by cockatoos, and the same is likely to apply to other larger hole nesters including Great Barbet.

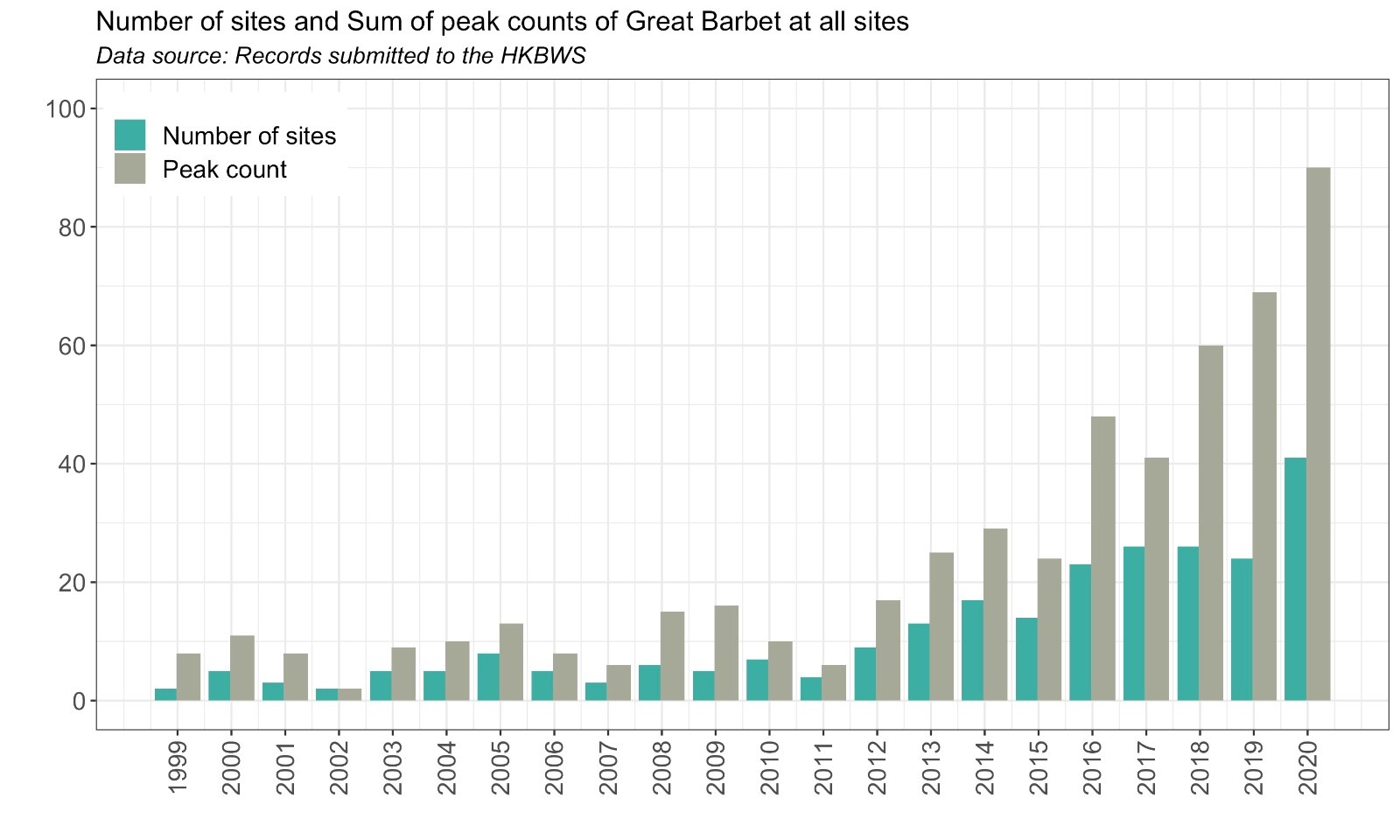

Population trends in HK other than HK Island since the first avifauana are unclear. The highest count during the 1958-98 period of 14 at Tai Po Kau on 21 May 1994 has not been bettered in the 1999-2020 period, during which the largest number seen were feeding groups of ten at Tai Po Kau Headland on 11 October 2018 and 21 July 2019. However, Figure 1 suggests that both range and numbers have greatly increased this century, though the 2016-19 atlas surveys may have affected reporting rates.

Herklots (1953) considered that Great Barbet was commoner in HK in summer than winter, implying that it was a partial migrant. This seems unlikely, as none of the Megalaimidae make anything other than limited altitudinal movements (Short and Horne 2001), and all subsequent authors agree that it is resident, albeit much more obvious during the spring and summer when it is most vocal.

However, it does show some capacity for dispersal: the HK Island population appears likely to have derived from 20th century colonists and it has recently reappeared there after being absent for over 24 years. In addition, two were noted at Mai Po, far from any regular sites, on 1 November 2016 and one was recorded at Discovery Bay, Lantau (the sole record from that island) on 2 July 2018. It also appears to have spread in Guangdong where it has been recorded as close to HK as Wutongshan (eBird 2023), and it is likely that cross-boundary movements take place.

BEHAVIOUR, FORAGING & DIET

Great Barbet is wholly arboreal and largely remains high in the tree canopy. It is usually solitary or found in pairs, but larger aggregations gather at fruiting trees, with up to ten having been found together in HK. Singing birds frequently vocalise from the same perch for long periods, while pairs frequently duet. It is rather sluggish and rarely seen in flight unless flushed; when this happens it usually drops from its perch and disappears into cover rather than flying for any distance in the open.

An insectivore-frugivore, the diet largely consists of fruit and large insects, whilst it has also been seen to eat a lizard Calotes versicolor (Carey et al. 2001). Fruits taken include those of Ficus, Bischofia and Litsea (Herklots 1953). Several birds often aggregate at fruiting trees, the largest recent concentrations (of up to ten birds on both occasions) were observed feeding on fruits of Ilex rotunda var. microcarpa and banyan Ficus sp. at Tai Po Headland in 2018 and 2019 respectively; similarly eight were observed feeding on fruit of a banyan Ficus sp. in Tai Po Kau Park in 2018. Barretto and Barretto (2020) also report it eating the fruit of ripe persimmon, Syzygium hancei and Photinia benthamiana.

BREEDING

The breeding cycle has been rather well-studied in HK (Hutson 1930, Benham 1960, Carey et al. 2001). There are seven confirmed breeding records, including two of double broods. Excavation of nest holes has been noted in April, copulation in early April and early July, incubation of first broods in May, (up to three) young noted in the nest up to 13 June and between 22 July and 13 August, and fledged young have been recorded between 6 June and 12 October. Nest holes, which may be entirely excavated by the birds themselves or may be modified natural holes, are in the trunks of trees (Grevillea sp. and Litsea monopetala have been used amongst others) and have been found between 3 m and more than 15 m above the ground.

RANGE & SYSTEMATICS

The range extends from north Pakistan in the west, across north India and Nepal and south through Myanmar, Thailand, north Laos and north Vietnam. It is widespread in the south and central China north to north Sichuan, south Shaanxi, Hubei, Anhui and Jiangxi Provinces but is absent from both Hainan and Taiwan (Krishnan 2023, Liu and Chen 2021, eBird 2022).

There are six races, four of which occur in China: P. v. marshallorum in south Tibet, P. v. magnificus and P. v. clamator in west Yunnan, and the nominate race throughout the remainder of the Chinese range, including HK (Cheng 1987).

CONSERVATION STATUS

IUCN: Least Concern. Population trend decreasing.

Figure 1.

Andersson, A. L. A. (2021). Ongoing and emergent threats to Yellow-crested Cockatoos (Cacatua sulphurea): a critically endangered species surviving in a city. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Hong Kong.

Barretto, K. and R. Barretto (2020). Bird of the Month. Great Barbet (Psilopogon virens virens). Hong Kong Gardening Society Newsletter, Apr. 2020.

Benham, M. E. M. (1960). Notes on nest of Chinese Barbet (Megalaima virens virens). Hong Kong Bird Report 1959: 62-72.

Cheng, T. H. (1987). A Synopsis of the Avifauna of China. Science Press, Beijing.

Dove, R. S. and H. J. Goodhart (1955). Field observations from the Colony of Hong Kong. Ibis 97: 311-340.

eBird. 2023. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed: 27 December 2023).

Herklots, G. A. C. (1933). Birds of Hong Kong. Part XIII. Family Capitonidae. The barbets. Hong Kong Naturalist 4: 83-84.

Herklots, G. A. C. (1953). Hong Kong Birds. South China Morning Post, Hong Kong.

Hutson, H. P. W. (1930). Notes and comments. Ornithology. Hong Kong Naturalist 1: 35-40.

Krishnan, A. (2023). Great Barbet (Psilopogon virens), version 2.0. In Birds of the World (N. D. Sly, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.grebar1.02

Liu, Y. and S. H. Chen (eds) (2021). The CNG Field Guide to the Birds of China (in Chinese). Hunan Science and Technology Publication House, Changsha.

Short, L. L. and J. F. M. Horne. (2001). Toucans, Barbets and Honeyguides. Ramphastidae, Capitonidae and Indicatoridae. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Walker, F. J. (1958). Field observations on birds in the colony of Hong Kong. Hong Kong Bird Watching Society, Hong Kong. (duplicated)