Tristram’s Bunting Emberiza tristrami 白眉鵐

Category I. Uncommon winter visitor to closed-canopy woodland and shrubland, scarce passage migrant in a wider variety of wooded habitats.

IDENTIFICATION

Feb. 2007, Martin Hale. Male.

14-15 cm. Adult male in breeding plumage distinctive with black head and throat apart from white crown stripe, supercilium and submoustachial and slightly paler ear coverts that have a white spot in the rearmost corner. Adult males in non-breeding plumage have black areas obscured by paler fringes that wear off during the winter.

Mar. 2023, Roman Lo. Female.

Females have broad and dark lateral crown stripes, a darker surround to the ear coverts, off white throat, brownish ear coverts and less richly-coloured flanks. The uppertail coverts and broad tertial fringes are rusty.

VOCALISATIONS

The call is higher-pitched and thinner than many other buntings.

When alarmed the same call is repeated at short intervals.

DISTRIBUTION & HABITAT PREFERENCE

Tristram’s Bunting is largely restricted to forest and older closed-canopy shrubland and is most often found in such areas of the Tai Mo Shan massif and the western New Territories at Tai Lam Chung. However, this is at least partly a function of observer coverage, and it may be equally common in less well-watched areas. It also occurs regularly in older shrubland, (e.g., HK Island country parks and Kadoorie FBG) and in younger woodland at such sites as Pak Sha O, but densities appear to be lower and wintering birds appear to favour older forests.

OCCURRENCE

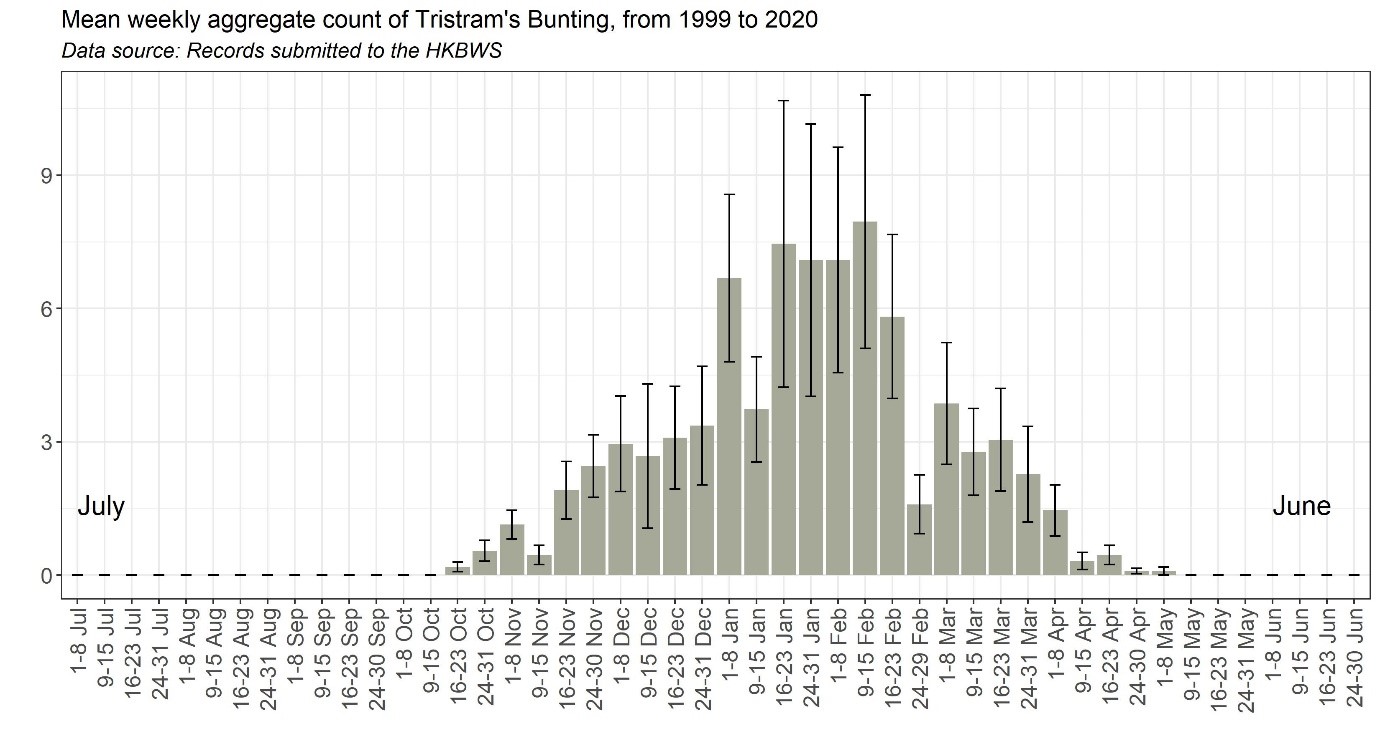

Tristram’s Bunting is a rather late migrant, the earliest reports being of single birds on 20 October 2007 and 2012. Figure 1 indicates that numbers remain low until the third week of November and peak in January and the first three weeks of February. The third week of February appears to signal a departure in most years and numbers decline slowly to the first week of April. A weak passage is evident in April when occasional birds are recorded from atypical sites such as the offshore islands, urban parks and the Deep Bay marshes.

On Po Toi, where it appears to be largely a migrant, it has occurred from 12 March to 1 May (the latest spring record in HK) and from 20 October to 11 December; in addition, there are a few winter records.

Whilst it can usually be found at its favoured sites at appropriate seasons, counts are not usually large, the highest being 37 in Tai Lam CP on 29 January 2020. An exceptional, and so far, unique influx of this species occurred during early January in 1992 that was directly associated with a northerly replenishment of the northeast monsoon but was considered by Lam and Williams (1994) to have perhaps been the consequence of the cumulative impact of cold surges in January following exceptionally mild conditions in December 1991. Trapping data from suggests a high degree of site fidelity both within and between seasons. Numbers recorded each winter are somewhat variable and appear to depend in part at least on how cold the weather is.

Tristram’s Bunting was not recorded from the Pearl River area by either Swinhoe (1861) or Kershaw (1904). Perhaps more surprisingly, it appears to have been overlooked by Vaughan and Jones (1913) despite their extensive fieldwork at Ding Hu Shan, though it was listed for Guangdong by La Touche (1925-30). The first confirmed record of this species here occurred at HK University on 27 February 1958.

It seems likely that the limited number of records during the 1960s was due to observers being unfamiliar with this species and its habitat preferences, in addition to the smaller area of closed-canopy woodland at the time. Furthermore, it is possible that the increase in numbers recorded in the past 20 years is due to increased observer activity, and thus it would appear there has been little change in its status in HK.

BEHAVIOUR, FORAGING & DIET

Tristram’s Buntings are usually to be found in parties of up to ten birds foraging for fallen fruit or invertebrates on the forest floor or eating grass seeds on quiet paths or roadsides.

RANGE & SYSTEMATICS

Monotypic. Breeds in Ussuriland, Russia and adjacent parts of northeast China; winters largely in south and southwest China but is recorded as an occasional winter visitor as far north as Beijing (Copete 2020, Liu and Chen 2021, Birding Beijing 2022).

CONSERVATION STATUS

IUCN: Least Concern. Population trend stable.

Figure 1.

Aylmer, E. A. (1932). Notes and Comments. Ornithology. Hong Kong Naturalist 3: 64-67.

Birding Beijing (2022). https://birdingbeijing.com/the-status-of-the-birds-of-beijing/ (Accessed 27 June 2022).

Copete, J. L. (2020). Tristram's Bunting (Emberiza tristrami), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.tribun1.01

Dove, R. S. and H. J. Goodhart (1955). Field observations from the Colony of Hong Kong. Ibis 97: 311-340.

Herklots, G. A. C. (1953). Hong Kong Birds. South China Morning Post, Hong Kong.

Herklots, G. A. C. (1967). Hong Kong Birds (2nd ed.). South China Morning Post, Hong Kong.

Kershaw. J. C. (1904). List of birds of the Quangtung Coast, China. Ibis 1904: 235-248.

La Touche, J. D. D. (1925-30). Handbook of the birds of Eastern China Vol. 1. Taylor and Francis, London.

Lam, C. Y. and M. D. Williams (1994). Weather and bird migration in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Bird Report 1993: 139-169.

Liu, Y. and S. H. Chen (eds) (2021). The CNG Field Guide to the Birds of China (in Chinese). Hunan Science and Technology Publication House, Changsha.

Swinhoe, R. (1861). Notes on the ornithology of Hong Kong, Macao and Canton, made during the latter end of February, March, April and the beginning of May 1860. Ibis 1861: 23-57.

Vaughan, R. E. and K. H. Jones (1913). The birds of Hong Kong, Macao and the West River or Si Kiang in South-East China, with special reference to their nidification and seasonal movements. Ibis 1913: 17-76, 163-201, 351-384.